Gilbert McInnis

Copyright 2005 Heldref Publications. First published in Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 46.4 (Summer 2005): 383-396.

The first is what I have called the mystical function: to waken and maintain in the individual a sense of awe and gratitude in relation to the mystery dimension of the universe, not so that he lives in fear of it, but so that he recognizes that he participates in it, since the mystery of being is the mystery of his own deep being as well. [...] The second function of a living mythology is to offer an image of the universe that will be in accord with the knowledge of the time, the sciences and the fields of action of the folk to whom the mythology is addressed. [...] The third function of a living mythology is to validate, support, and imprint the norms of a given, specific moral order, that, namely, of the society in which the individual is to live. [...] And the fourth is to guide him, stage by stage, in health, strength, and harmony of spirit, through the whole foreseeable course of a useful life. (221/222)

Joseph Campbell, Myths To Live By (221-22)

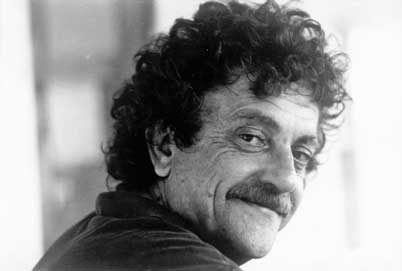

Campbell's description of the four functions of a mythology reflects the extent to which the theory of evolution functions as a mythology in the lives of Kurt Vonnegut's characters–Mary Hepburn (Galàpagos), Unk (The Sirens of Titan), Billy Pilgrim (Slaughterhouse-Five), Howard Campbell (Mother Night), and Dwayne Hoover (Breakfast of Champions)–and in the American culture depicted by Vonnegut's novels.

In Galápagos, the notion of natural selection discloses a world of mystery and awe, and we observe this wonder when we examine the chance element in natural selection. According to what we learn from Galápagos, the chance element in natural selection shares characteristics with the mystery element of God, and therefore is a possible surrogate for that mystery. However, the characters are not active participants in that mysterious “dimension of the universe,” but rather are victims of the deterministic force underlying the chance mechanism of natural selection. When we further examine that malicious force, we conclude that it, too, resembles the mechanistic view of the universe propounded by evolutionary science. Therefore, the cosmological function of evolutionary mythology “offers an image of the universe that is in accord with” evolutionary science.

Vonnegut's readers experience the power or awe in Darwin's notion of natural selection in Galápagos. Leon accents this omnipotent power when he says, “I am prepared to swear under oath that the Law of Natural Selection did the repair job without outside assistance of any kind” (291). That “repair job” is natural selection's “job” of correcting human evil: At the outset of Galápagos, Vonnegut portrays the “big brains” destroying the earth and humanity, yet later, through the material workings of natural selection, these big brains evolve to “smaller skulls,” and consequently the planet and humanity are saved from destruction. Some may argue that Mary plays an important role in this new creation, because her genetic engineering creates a new family that survives the apocalypse. However, Mary does so by the prodding of her big brain, which natural selection also repairs. Therefore, we are led to believe that natural selection alone is an almighty power that governs humanity and the universe.

Furthermore, according to the image the novel impresses on us, the universe is determined by chance, and evolutionary science is employed to validate this image so that the mythology will be in accord with the prevalent ideas of our time. Leon tells us that natural selection played a mysterious role in correcting human evil, but we conclude that natural selection operates according to the force of chance. Moreover, chance is portrayed as a materialistic alternative to the mysterious role of God. Philip Johnson asserts that “[a] materialistic theory of evolution [...] must be based on chance, because that is what is left when we have ruled out everything involving intelligence or purpose” (22). According to Leon, and Philip Johnson, either the universe is governed by chance or God, but not both, because, as R.C. Sproul states, “If chance existed, it would destroy God's sovereignty. If God is not sovereign, he is not God. If he is not God, he simply is not. If chance is, God is not. If God is, chance is not. The two cannot coexist by reason of the impossibility of the contrary” (3; emphasis added). Moreover, Mary Midgley, discussing the popular evolutionist Jacques Monod and his book, Chance and Necessity, helps us to understand how his philosophy of chance is also evident in the gambling-casino-luck view of the universe depicted in Galápagos. Midgley also asserts that “Monod's interest in contingency, however, does not center on this causal disconnection between elements of matter, but on the removal of God” (41). Thus, according to Midgley and Monod, accepting the sovereignty of chance undermines the belief in God's existence. In fact, Boodin advocates that when this happens, chance becomes our new god. He states:

By some magic the antecedent factors [of evolution] are supposed to yield new forms and characters. By chance variation the structure of protoplasm is supposed to build up from inorganic matter, and by further chance variation the various life characters and forms appear. Intelligence is but a favourable chance variation of material antecedents. Chance is God. (82)

Evolutionary science is employed to validate such an image of the universe so that the mythology will accord with the prevalent ideas of our time because, as Monod argues, “Chance alone is at the source of every innovation, of all creation in the biosphere. Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, at the very root of the stupendous edifice of evolution [...] is today the sole conceivable hypothesis, the only one that squares with observed and tested fact” (112, emphasis in original). Therefore, according to Leon, our observations of Mary, and Monod's image of the universe, “chance alone” is at the source of every innovation, of all creation; and evolutionary science is employed to validate such a mythology so it will be accepted by our current culture as tested fact.

However credible Darwin's notion of natural selection is, whether in the sciences or in culture, it fails to serve a fundamental role pertinent to a mythology, especially when the characters cannot participate in its “mystery of being.” Hence, this mystery of being is not connected to the character's deep sense of being, but is a disconnected and fatalistic force that determines the course of evolution without any consideration of horizontal or vertical relationship. Consequently, when the characters believe in the evolutionary mythology, they live according to its materialistic principles, or the chance mechanism of natural selection. In comparison to a Greek-Calvinistic view of characters as mere actors on a stage, the evolutionary mythology would have us believe now that we are nothing more than mere cogs in a machine.

Both Unk (The Sirens of Titan) and Billy Pilgrim (Slaughterhouse-Five) experience the awe of their chance-driven universe, yet like Leon and Mary, they do not participate in that “mystery dimension” because a mechanistic and deterministic philosophy characterizes the “mystery” depicted in both The Sirens of Titan and Slaughterhouse-Five. Unk has a revelation that provides a description of that awe governing his life when he claims, “I was a victim of a series of accidents [...a]s are we all.” His final revelation exemplifies how the random impersonal force, or chance, not only governs his universe but governs the human biological dimension as well. About the accidents that Unk had while in the chrono-synclastic infundibula, Rumfoord asks, “Of all the accidents which would you consider the most significant?” Unk “cocked his head and said, ‘I'd have to think—'.” However, Rumfoord provides the explanation when he says, “I'll spare you the trouble [...]. The most significant accident that happened to you was your being born” (258/9). Unk's initiation into the chrono-synclastic infundibula brings together a cosmogonic experience (typified by his statement: “I was a victim of a series of accidents”) and an origins experience (Rumfoord explains to him that his biological birth was also an accident). Unk does not experience these two revelations until he has been “baptized” into the chrono-synclastic infundibula, which functions as a syncretic element of myth, because the cosmic and biological elements of the evolutionary mythology merge here. Moreover, Vonnegut's invention of the chrono-synclastic infundibula shares traits with his notion of “unstuck in time” from his later novel, Slaughterhouse-Five.

Like Unk, Billy has an epiphany when he becomes “unstuck” in time. Billy's subsequent quest helps us come to terms with the antagonism between chaos and order, but Vonnegut synthesizes the theories of Einstein and Darwin in the fictional invention of unstuck in time. After Billy's initiation of becoming unstuck in time, the Tralfamadorians teach him that there is no beginning, middle, or end to life. “There isn't any particular relationship between all the messages [...]. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral” (88). Moreover, Boodin argues that this “modern point of view which finds its typical expression in Darwinism [...] runs on like an old man's tale without beginning, middle, or end, without any guiding plot. It is infinite and formless. Chance rules supreme. It despises final causes” (77). Hence, Billy believes in no initial cause or final cause, or a God, but instead, his realization leads him to concur that “chance rules supreme” in the universe.

Moreover, Billy does not participate in that mystery dimension of chance because as the opening page of The Sirens of Titan declares, “Everyone now knows how to find the meaning of life within himself.” For Unk's part, his epiphany is a summation of his lifelong journey, climaxing with his understanding that he cannot relate to that impersonal force or awe because it is beyond his control. Therefore, like Unk, Billy can only conclude that “everything is all right, and everybody has to do exactly what he does” (198), or as he learns from the Tralfamadorians, “‘Well, here we are, Mr. Pilgrim, trapped in the amber of this moment. There is no why'” (76). In fact, when “chance rules supreme [...] there is no why” because as Sproul argues, “To say that something happens or is caused by chance is to suggest attributing instrumental power to nothing” (13). If the myth of chance is allowed to govern our beliefs, then there is no meaning to life, because we are “attributing instrumental power to nothing.” In “Vonnegut's Invented Religions as Sense-Making System,” Peter Freese argues a similar point: “Billy attempts to teach his fellow humans that their repeated question ‘Why?' is useless and inappropriate” (155). Moreover, the question “Why?” is useless and inappropriate for both Billy and Unk because there is no “mystery dimension of the universe” other than the awe of nothingness or chaos, and this meaning is justified in terms of evolutionary science. Therefore, both novels investigate how evolutionary science provides a cosmological function that is in accordance with the prevalent ideas of our time, but the two novels also reveal how myth is sanctioned by the principles of evolutionary science.

Through Howard Campbell's description of the force underlying the totalitarian mind (wartime Nazi Germany in Mother Night), the mystical function of the evolutionary mythology depicts how chance rules supreme. As in other novels, Vonnegut portrays a chance element in Mother Night, and also as in the previous novels, it is portrayed as a substitute for God. Moreover, like our previous characters, Campbell does not participate in “relation to the mystery dimension” of that chance-driven universe because the “mystery of being” that governs his universe operates according to the terms of contemporary evolutionary science. Like the big brains in Galápagos, the human mind in Mother Night operates as a simulacrum of the mechanical and random universe, and this mechanical, random thought machine is described by Campbell as a totalitarian mind. Moreover, as with the big brains in Galápagos, each totalitarian mind that is transformed by that random thought machine in Mother Night is the result of an “awful” force that we have observed operating in Vonnegut's The Sirens of Titan and Slaughterhouse-Five. According to Campbell, the totalitarian mind is “a mind which might be likened unto a system of gears whose teeth have been filed off at random. Such a snaggle-toothed thought machine, driven by a standard or even substandard libido, whirls with the jerky, noisy, gaudy pointlessness of a cuckoo clock in Hell” (162). Therefore, the human mind is likened to a universe or thought machine that operates randomly, a view of the universe also espoused by evolutionary science. The totalitarian mind, or that force guiding the universe, is responsible for much of the chaos depicted in the novel; and Campbell is in awe of its power to transform the human mind. He informs us:

That was how my father-in-law could contain in one mind an indifference toward slave women and love for a blue vase—

That was how Rudolf Hoess, Commandant of Auschwitz, could alternate over the loudspeakers of Auschwitz great music and calls for corpse-carriers—

That was how Nazi Germany could sense no important difference between civilization and hydrophobia—

That is the closest I can come to explaining the legions, the nations of lunatics I've seen in my time. (162-163)

Therefore, that random thought machine not only governs the universe, but conditions the totalitarian minds of Campbell, Campbell's father-in-law, Rudolf Hoess, and “nations of lunatics.”

However meaningless the “God of Chance” appears in Mother Night, the characters nevertheless attempt to participate in relation to its “mystery dimension.” They do so by way of adaptation, but as they adapt, the nature of their transformation signals the power they relinquish to this random thought machine to transform their minds into totalitarian minds. For example, at the beginning of the story, before the war, Campbell is a successful playwright, but once the war begins, he makes a double adaptation: he transforms into a radio propagandist for Hitler and_to secure his future after the war_an American agent. However, his various adaptations, or series of accidents, make him schizophrenic. Schizophrenia, the “first fruit” of his new totalitarian mind, eventually leads to his destruction. Campbell's sister-in-law, Resi, concludes: “He is so used up that he can't love any more. There is nothing left of him but curiosity and a pair of eyes” (166). Like Campbell, “nations of lunatics” in Mother Night fail to participate in that mystery dimension of the universe, precluded by their successful adaptation to the ruling mythology of social Darwinism. Therefore, according to Galápagos, The Sirens of Titan, Slaughterhouse-Five, and Mother Night, the universe operates according to the material principles of a chance mechanism or Darwin's notion of natural selection.

In addition, the cosmological function of the evolutionary mythology, or the random thought machine, is justified by evolutionary science's explanation of the constitution of the universe, and is, therefore, relevant to our time. First, as mentioned above, the totalitarian mind, or that random thought machine of the universe, not only governs the universe, but conditions Campbell, Campbell's father-in-law, Rudolf Hoess, and nations of lunatics. Moreover, the science of social Darwinism also makes the evolutionary mythology relevant to our time. Campbell's radio broadcasts propagate a mythology so that “Nazi Germany could sense no important difference between civilization and hydrophobia,” or between civilization and an environment that would sanction the killing of millions of so-called inferior human beings. But the Nazi mythology justifies, or makes relevant, his message, or truth. According to the social Darwinist Dr. Jones, Campbell was brave enough to “tell the truth about the conspiracy of international Jewish banking and international Jewish Communists who will not rest until the bloodstream of every American is hopelessly polluted with Negro and/or Oriental blood” (56). Moreover, referring to Jones's fascist newspaper, Campbell informs us that the articles were “coming straight from Nazi propaganda mills,” and that it “is quite possible, incidentally, that much of his more scurrilous material was written by me” (60). Finally, the biological racism or Nazi Mythology “was developed from the theory of eugenics developed by Charles Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton” (Bergman 109). Therefore, it is possible for anyone, including scientists, to develop a mythology from evolutionary science.

In Breakfast of Champions, we observe how the principal character Dwayne Hoover is controlled by the “awe-full” power of materialism and how it transforms his mind. Like Vonnegut's other characters we have discussed, he does not participate in “relation to the mystery dimension” of this materialistic universe, but is instead a victim of its deterministic force. Kilgore Trout exemplifies the “awe-full” power of this materialistic dimension of the universe when he claims, “There were two monsters sharing the planet with us when I was a boy [...]. They were determined to kill us, or at least to make our lives meaningless [...]. They inhabited our heads. They were the arbitrary lusts for gold, and God help us, for a glimpse of a little girl's pants” (25; emphasis added). According to Trout, “arbitrary” nature characterizes this mysterious power. And as with other Vonnegut characters, this arbitrary mystery inhabits Dwayne's head. His “incipient insanity was mainly a matter of chemicals, of course. Dwayne Hoover's body was manufacturing certain chemicals which unbalanced his mind” (14). However, if, according to evolutionary science, natural selection determines the course of all material things in the natural world, then Dwayne's “unbalanced mind” is determined by it, too. His mind is controlled arbitrarily, like the “big brains” in Galápagos, or the totalitarian minds in Mother Night.

These arbitrary bad chemicals that determine Dwayne's mind to do bad things cause many other minds to do evil as well.

Dwayne certainly wasn't alone, as far as having bad chemicals inside of him was concerned. He had plenty of company throughout history. In his lifetime, for instance, the people in a country called Germany were so full of bad chemicals for a while that they actually built factories whose purpose was to kill people by the millions. The people were delivered by trains. (133)

Moreover, Vonnegut's narrator makes it clear that these bad chemicals are not drug-induced, but created by the natural functions of the body. “A lot of people were like Dwayne: they created chemicals in their own bodies which were bad for their heads” (70).

Dwayne behaves according to the materialistic principles of evolutionary science, but he does not participate in that mysterious dimension of the universe. In his relationship with Francine Pefko, we see that they cannot exercise free will, but behave according to the principles of materialism. Shortly after Dwayne and Francine have sexual intercourse, Vonnegut's narrator gives one material yet metaphysical reason for Dwayne's suffering. “Here was the problem: Dwayne wanted Francine to love him for his body and soul, not for what his money could buy. He thought Francine was hinting that he should buy her a Colonel Sanders Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise” (157). Hence, Dwayne fails to meet his “invisible need” because the malicious force of materialism prevents him and Francine from participating in a meaningful relationship. The evolutionist Richard Lewontin claims this is because Dwayne exists as one of many material beings “in a material world, all of whose phenomena are the consequences of material relations among material entities” (Johnson 70). In brief, Dwanyne must come to terms with Lewontin's materialistic cosmogony is what Dwayne must come to terms with by the end of Breakfast. He cannot meet his immaterial needs by attempting to solve his problems according to the rules of an arbitrary materialistic world view.

Moreover, this arbitrary and materialistic understanding of the universe by which Dwayne and others live by in Breakfast of Champions live derives its credibility from the scientific materialism of evolutionary science, which is in accord with the prevalent ideas of our time. The two monsters that Trout says are determined to kill the human race_the desire for gold and “a glimpse of a little girl's pants”_are materialistic pleasures derived from materialistic values, or a logical manifestation of scientific materialism. According to Runes, materialism is “a proposition about values: that wealth, bodily satisfactions, sensuous pleasures, or the like are either the only or the greatest values man can see or attain”. Furthermore, scientific materialism is the belief that “the universe is not governed by intelligence, purpose, or final causes” but “that matter [money or sex] is the primordial or fundamental constituent of the [human] universe” (Runes 189). Money and sex seem to be the fundamental constituents of the universe of Breakfast. Hence, scientific materialism, or evolutionary science, serves the cosmological function in the novel because it explains the constitution of the universe, in a way that makes the mythology practical for the characters.

Joseph Campbell's third and fourth functions of a mythology are “to validate, support, and imprint its norms of a given, specific moral order [...] of the society in which the individual is to live,” and “to guide [the individual] stage by stage in health, strength, and harmony of spirit throughout the [...] course of useful life.” If Campbell is correct, the sociological function of the myth should “validate, support, and imprint” a certain social order and the pedagogical function should instruct individuals how to live “in health, strength, and harmony of spirit.” However, we have concluded that the social organization that is informed by the evolutionary mythology is justified by the ideology of Darwin's notion of natural selection, or the notion of survival of the fittest. For some individuals, an equal treatment of Darwin's notion of natural selection and the notion of survival of the fittest may seem far-fetched, but Darwin in The Origin of Species often used the two terms interchangeably. He states that the “preservation of favourable individual differences and variations, and the destruction of those which are injurious, I have called Natural Selection, or the Survival of the Fittest” (89). Therefore, the social or moral implications of the notion of survival of the fittest would be the same for the notion of natural selection.

One essential human value that is supported and validated by Darwin's notion of the survival of the fittest is also depicted in the Vonnegut novels under discussion, most directly in the opening page of The Sirens of Titan. This value asserts that human beings will not find meaning “out there,” but instead must look within themselves and that to become the fittest, individual interest must be the supreme goal. Moreover, through by the survival of the fittest mythology, each individual's reliance on a meaningful relationship with a human community is transformed into an overburdened self-reliance on individualism. If there is to be a relationship with someone “out there,” it is either to procreate individual genes or to consume pleasure. Vonnegut's characters are ill-served by allowing themselves to let Darwin's evolutionary mythology or the survival of the fittest validate their moral order and guide them stage by stage throughout the course of their lives. The resulting moral order, making individual interests the supreme goal, negates human connectedness to a larger pattern or the human community.

In Galápagos, Mary's decision to create a new race is supported and validated by a Darwinian social order, or the materialistic morality of survival of the fittest, and that order or morality guides her stage by stage in strength throughout life. According to the sociological function of the evolutionary mythology, Mary, following Darwin, must preserve the “favourable individual differences and variations” and allow for the “destruction of those which are injurious.” She accomplishes this by creating a new race out of the genetics of the innocent simple folk Akiko and Kamikaze. However, as Leon informs us, Darwin's notion of natural selection or the survival of the fittest guides Mary's “big brain,” and by this guidance, she accomplishes the repair job for all of humanity. Also, when Mary learns that there is a classification between favourable individuals and injurious ones, we learn “how to live a human lifetime under these circumstances.” We learn that to evolve in a world dominated by these values, we must, like Mary, accept that classification.

Although Vonnegut exploits Darwin's notion of a superior race for his fictive purpose, this idea or ideology has mythic implications according to Northrop Frye. He states: “The coming of mythical analogies to evolution in the nineteenth century [...or] what is called social Darwinism, for instance, tried to rationalize the authority of European societies over ‘inferior' ones” (174). According to Frye, the belief that Europeans are superior to savages is mythic in itself. He also points out how this ideology becomes a “popular mythology” that can be used to “rationalize the authority of European societies over ‘inferior' ones” like that of Akiko and Kamikaze. Therefore, according to Vonnegut's Galápagos and the evolutionary mythology, a specific moral order can be derived from the science of Darwin's notion of the survival of the fittest, and it can guide individuals “stage by stage” in “strength” through the whole foreseeable course of a useful life. However true this moral order is, it nevertheless reduces society to tribalism or harsh individualism, because, as Darwin argues, natural selection, or the central mechanism of the evolutionary mythology, must preserve “favourable individual differences and variations” and destroy “those which are injurious.”

However, Vonnegut rejects this harsh individualism or tribalism when, by inversion, he parodies in Galápagos the European element in Darwin's myth. Moreover, Vonnegut's inversion or perversion of Darwin's narrative adds an ironic element to his novel. Mary Hepburn is of European descent, and the common progenitor of Akiko's descendants. Instead of beginning the story of evolution with the savage Akiko and ending it with the superior European Mary Hepburn (as Darwin's myth does), Vonnegut reverses Darwin's line of descent by beginning it with Mary and continues it with Akiko and her descendants. In doing so, Vonnegut rejects the myth or morality that Europeans are superior to savages. Moreover, he constructs his narrative so that the European white savagery is repaired instead (ironically, by Darwin's notion of natural selection) by evolving to innocent fisherfolk. Hence, Vonnegut feels that those who have invented a myth to dominate other races in the name of evolutionary science are injurious to the whole of humanity.

In The Sirens of Titan and Slaughterhouse-Five, the same evolutionary science sanctions a Darwinian morality in the societies portrayed, and this evolutionary morality instructs both Unk and Billy about how to live. As in Galápagos, the specific moral order derives its justification from Darwin's notion of natural selection. Unk, the principle character in Sirens, no longer believes in an absolute moral authority “out there” and therefore in no absolute universal meaning. Yet, the opening page of Sirens declares, “Everyone now knows how to find the meaning of life within himself.” The key word to understanding the sociological change that Unk's society is undergoing is “now.” It implies that society has changed since the Second World War, and the cause of that change is probably due to the impact of evolutionary science on the human condition. As Vonnegut's narrator in Galápagos declares of Darwin (and I agree), “He thereupon penned the most broadly influential scientific volume produced during the entire era of great big brains. It did more to stabilize people's volatile opinions of how to identify success or failure than any other tome” (13). Consequently, the meaning of life in Sirens is “now” sought within oneself and not “out there” in the community, or even in a realm beyond the natural confines of the human brain.

Moreover, Unk principally learns this evolutionary morality principally from an experience he has in the chrono-synclastic infundibula, which is also a popular form of moral relativism. According to the chrono-synclastic infundibula, “there are so many different ways of being right” (9). Therefore, according to the morality Unk experiences there and to the declaration in the opening page of Sirens declares, “Everyone now knows how to find the meaning of life within himself.” This belief engenders a social order in the novel that is sanctioned by Darwin's notion of natural selection. First, we read on the opening page of the novel that “[w]hat mankind hoped to learn in its outward push was who was actually in charge of all creation, and what all creation was all about.” Unk learns that the meaning of life is within himself, but he is instructed “what all creation was about” after he experiences the chrono-synclastic infundibula. That experience teaches him that “I was a victim of a series of accidents [...] As are we all.” Hence, Unk learns the cosmic explanation sanctioned by Darwin's ideology of natural selection. Also, the pedagogical function of the mythology, or the ideology of the phrase “I was a victim of a series of accidents [...] As are we all,” informs him how to live stage by stage under his evolutionary circumstances. For example, if his life is determined by accidents, then he has no free will and is not responsible for his actions. That is why the meaning of life is reduced to his own individual interpretation, which is nothing other than moral relativism. Consequently, moral relativism, or “the different ways of being right,” or that meaning within himself, guides him in life, sanctioned by the science of evolution_or that “series of accidents.”

Similarly in Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy understands the sociological implications of the evolution mythology. For him too, there is no God, and therefore no universal morality governing his life and his universe. In Billy's universe, Darwinian ideology is replaces God or any absolute universal meaning. The Tralfamadorians instruct him first about this when they tell him about their system of beliefs, “There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects” (88). However, the Tralfamadorian mythology can be explained in terms of Darwin's ideology. Boodin states that according to Darwinism, “History runs on like an old man's tale without beginning, middle, or end, without any guiding plot. It is infinite and formless...” (77). According to Boodin's view of Darwinism and the Tralfamadorian mythology history is infinite and has no “beginning, middle, or end.” Because there is no first cause, or final cause, “Chance is God.” Moreover, if Chance is God, then, as Vonnegut's narrator concurs, there is no moral to be learned in this “certain social order” other than that our lives, fundamentally, are explained in terms of a series of accidents or Darwin's notion of the survival of the fittest. In this way, Darwin's notion of survival of the fittest becomes the existing morality.

Like Unk's experience in the chrono-synclastic infundibula, Billy's becoming unstuck in time (a “time” that has no beginning, middle, or end) symbolizes his entry into the Darwinian order, and like Unk, Billy also experiences a “baptism” into moral relativism. Moreover, once Billy becomes unstuck in time, the Tralfamadorians instruct him on how to live according to these circumstances. They teach him that in life, “[t]here is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects” (88); that “[a]ll moments, past, present, and future always have existed, always will exist” (26). However, Boodin, discussing S. Alexander's Space, Time and Deity, states that

The abstractions of space and time are invested with metaphysical properties which have nothing to do with the mathematical origin of these concepts. Space becomes a metaphysical continuum and not just a mathematical continuum, and thus space furnishes continuity to the instants of time. Space also has the property of conserving the instants of time. Space furnishes the continuity and time the content. (Boodin 87)

According to Alexander, time and content are inseparable, so becoming unstuck in time would also mean becoming unstuck in content. Thus, Billy's “unstuck” experience has loosed him from any absolute meaning. In fact, this is the philosophy that the Tralfs teach Billy: “There isn't any particular relationship between all the messages [...] There is [...] no [absolute] moral.” Moreover, once Billy “converts” to the Tralf mythology, he becomes unstuck to any content or meaning; therefore, the moral relativism of the evolutionary mythology replaces his absolute morality.

In Mother Night, the moral implications of evolution mythology impress on its central character, Howard Campbell, the specific social order of Darwin's ideology of survival of the fittest and instructs him “stage by stage” throughout the course of his life to adapt to his environment at all cost. Moreover, like Vonnegut's other characters, Howard Campbell suffers the gravest consequences when he lives according to the ideology of this mythology. For example, by the end of the novel, “He is so used up that he can't love any more. There is nothing left of him but curiosity and a pair of eyes” (166). His demise is the result of many precarious adaptations to the war-time environment of the novel. Before the war, he is a successful American-born playwright in Germany. Once the war begins, Campbell adapts to the role of a radio propagandist for Hitler; once the American government enters the war (and consequently threaten Hitler's success) Campbell adapts to the role of an American double agent. The evolutionary mythology or morality impressed upon him that it is more important to adapt to his environment and survive than to be loyal to one absolute position.

After there “is nothing left of him but curiosity and a pair of eyes,” Campbell blames these precarious adaptations on the Nazi totalitarian mind. However, on examining this totalitarian mind, we concluded that it is the ideology of social Darwinism that conditioned him. Campbell describes the totalitarian mind as follows: “I have never seen a more sublime demonstration of the totalitarian mind, a mind which might be likened unto a system of gears whose teeth have been filed off at random [...] The missing teeth, of course, are simple, obvious truths, truths available and comprehensible even to ten-year-olds, in most cases” (162). He admits that those teeth, or absolute truths, have been removed by a “random-thought” machine, or Darwin's mechanism of natural selection, and this “random-thought” machine conditions the whole culture depicted in the novel. Hence, as Campbell says, “That was how Nazi Germany could sense no important difference between civilization and hydrophobia” (163).

Moreover, Campbell tells us the extent to which social Darwinism has transformed Adolf Eichmann's mind into a totalitarian, “relativistic” mind: “I offer my opinion that Eichmann cannot distinguish right and wrong—that not only right and wrong, but truth and falsehood, hope and despair, beauty and ugliness, kindness and cruelty, comedy and tragedy, are all processed by Eichmann's mind indiscriminately” (123-4). Tragically, in embracing the Nazi mythology derived from social Darwinism, Eichmann, Hoess, Campbell's father-in-law, Nazi Germany, and Campbell have all explained any absolute morality indiscriminately, and now they must find their own relative meaning within themselves to survive, stage by stage, through the course of their lives.

In Breakfast of Champions, the evolution mythology sanctions a materialistic moral order in the American society portrayed by Vonnegut, and these materialistic values inform Dwayne Hoover “stage by stage” through the course of his life. Accordingly, in Breakfast, the evolutionary mythology imposes on the characters the belief that human value and self-worth increase proportionately with the accumulation of valuable possessions or measurable things; consequently, measurement and the accumulation of “things” toward an absolute amount of possessions will supposedly provide meaningful value. Dwayne's materialistic morality is evident when he reduces the meaning of happiness and fulfillment to bodily pleasures or the acquisition of material things. Dwayne owned

not only the Pontiac agency and a piece of the new Holiday Inn. He owned three Burger Chefs, too, and five coin-operated car washes, and pieces of the Sugar Creek Drive-In Theatre, Radio Station WMCY, the Three Maples Par-Three Golf Course, and seventeen hundred shares of common stock in Barrytron, Limited, a local electronics firm. He owned dozens of vacant lots. He was on the Board of Directors of the Midland County National Bank. (64-65)

Dwayne's wealth is large; he has consumed the whole city, and the value of his measure provokes awe in others. An employee who overhears Dwayne singing at the Holiday Inn comments, “If I owned what he owns, I'd sing, too” (41). Vonnegut portrays a materialistic moral order in Breakfast that captivates and controls many characters in the society. These materialistic values are sanctioned by the ideology of scientific materialism or a Darwinian “a priori commitment to materialism” (Johnson 76).

Moreover, Vonnegut would have us believe that scientific materialism provides the basis for his characters' values. Sallye Sheppeard states:

That the values fostered by science and technology prove more detrimental than beneficial to mankind also finds expression in Vonnegut's other early novels, but of these, Breakfast of Champions (1973) contains their grimmest exposé. Its setting and narrative clearly reflect the debilitating effects of contemporary American society, via science and technology, upon the human spirit. (17)

According to Sheppeard, contemporary American society lives by the “values fostered by science and technology,” leading us to conclude that when science sanctions these values, science functions like myth. Moreover, the Americans in Breakfast derive their values “according to certain rules” of science, and more specifically an evolutionary science. The “debilitating effects” of those rules on American society manifest themselves in the form of “popular” materialism.

The implications of these materialistic values raise new questions. First, for how long will Darwinist theory have an affect on our human geography? George Streeter provides at least one answer when he stated: “Our great [scientific] heroes are those who succeed in cleverly expressing the complex phenomena of nature in the form of precisely stated laws, or archetypal patterns, and we grade our heroes according to the length of time their laws or patterns endure” (405). Darwin's theory was published almost one hundred and fifty years ago (1859); earlier in this essay I quoted praise for Darwin by the narrator of Galápagos. To that statement, I would add that Darwin's Origin of the Species is also the most broadly influential scientific volume of the twentieth century and perhaps of decades to come.

A second question raised by this study is, will the evolution mythology replace the traditional Judeo-Christian mythology and become the dominant mythology in Western society? From what we have learned from Vonnegut's writings, the answer is “No”_unless those who espouse it can overcome three barriers mentioned by Suzi Gablik in Has Modernism Failed?:

Although we may value technological power more than sacred wisdom, scientific rationalism has so far failed to prove itself as a successful integrating mythology for industrial society; it offers no inner archetypal mediators of divine power, no cosmic connectedness, no sense of belonging to a larger pattern. (94; emphasis added).

The relevance of Gablik's three barriers (taken in reverse order) can be verified with examples from any of the novels studied in this essay. Unk's conversion to the evolutionary mythology provides “no sense of belonging to a larger pattern” because he now “knows how to find the meaning of life within himself” (1). In fact, examples from the other characters examined here_Mary Hepburn, Billy Pilgrim, Howard Campbell, and Dwayne Hoover_could also support this point. In the novels discussed, a “cosmic connectedness” appears to be operating within the evolutionary mythology, especially when we consider that Darwin's theory serves many mythological functions, but once these pertinent properties are raised from the deepest unconsciousness, the sole cosmic connectedness we find in the mythology is characterized by the material and ruthless workings of natural selection, hardly enough to keep a community together![1] The strongest example of “inner archetypal mediator of divine power,” in the novels is, again, natural selection. Although natural selection plays a pseudo-divine role in evolution mythology, in its apparent ability to select life or death, I conclude that Darwin's notion is no more than a materialistic replacement for the Judeo-Christian notion of the Holy Spirit. Natural selection impels us to reduce all the workings of the universe to materialistic ends, so there can be no mention of “spirit” or any teleological element in science per se.

Bergman, Jerry “The History of Evolution's Teaching of Women's Inferiority.” Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 48.3 (June 1992): 109-123.

Boodin John E. Cosmic Evolution. New York: Kraus Reprint Company, 1972.

Cambell, Joseph Myths To Live By. New York: Bantam Books, 1972.

Freese, Peter “Vonnegut's Invented Religions as Sense-Making System.” The Vonnegut Chronicles: Interviews and Essays. Ed. Peter J. Reed. Westport, CT : Greenwood, 1996.

Frye, Northrop Words with Power. Markham (Ontario): Viking, 1990.

Gablik, Suzi Has Modernism Failed. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1984.

Godawa, Brian Hollywood Worldviews. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2002.

Johnson, Phillip E. Objections Sustained. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998.

Midgley, Mary Science as Salvation: A Modern Myth and its Meaning. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Monod, Jacques Chance and Necessity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

Runes, Dagobert D. Dictionary of Philosophy. 15th edition: New York: Philosophical Library, 1960.

Sheppeard, Sallye “Kurt Vonnegut and the Myth of Scientific Progress.” Journal of the American Studies Association of Texas 16.1 (1985): 14-19.

Sproul, R.C. Not a Chance: The Myth of Chance in Modern Science and Cosmology. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books, 1994.

Streeter, George L. “Archetype and Symbolism.” Science 65.1687 (Apr. 29, 1927): 405-412.

Vonnegut, Kurt, Jr. Galápagos. New York: Dell Publishing, 1985.

---. Breakfast of Champions. New York: Dell Publishing, 1973.

---. Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Dell Publishing, 1969.

---. Mother Night. New York: Dell Publishing, 1962.

---. The Sirens of Titan. New York: Dell Publishing, 1959.

[1] However, a recent computer-animated film, Dinosaur, written by John Harrison (1999), is a clever expression of the newer neo-Darwinian (and more politically correct) notion of evolution through cooperation rather than the old Darwinian concept of competition (Godawa, 122)

Gilbert McInnis has written four full-length plays, amongst which The Die is Cast, has been published, as well as a a collection of poetry "Life Along the River", and a collection of short stories.

Video presentation (Windows Media Video format): Evolutionary Mythology in the Writings of Kurt Vonnegut, by Gilbert McInnis, PhD.